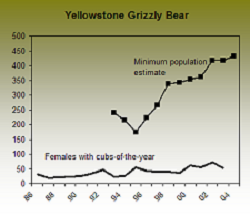

The first time I saw a grizzly in the wild was in 1999 while leading an Outward Bound expedition in the Beartooth Mountains just north of Yellowstone National Park (YNP). Seeing a grizzly on foot brings with it adrenaline and fear, but also an inexplicable wonder and affinity. At the time, the grizzly population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE, comprised of YNP, Grand Teton National Park (GTNP), and surrounding national forests) was approximately 300 bears.  We didn’t even carry the large bottles of pepper spray that are now requisite in the backcountry. Since 1975, when there were as few as 136 bears in YNP and grizzlies were first given federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, the grizzly population has climbed significantly. Today, the population of the GYE is estimated to be between 700 and 1,100 bears (depending on the source and estimation method).

We didn’t even carry the large bottles of pepper spray that are now requisite in the backcountry. Since 1975, when there were as few as 136 bears in YNP and grizzlies were first given federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, the grizzly population has climbed significantly. Today, the population of the GYE is estimated to be between 700 and 1,100 bears (depending on the source and estimation method).

My most recent grizzly sighting was not in person, but with a game camera. Last fall, a friend found a large bull moose that had recently died near a local creek. After examining the carcass with a GTNP biologist, we installed a game camera to see what would find this valuable food source. Hours after we left, the camera caught a mother sow and two cubs of the year, who had likely found the carcass by smell. The bear family enjoyed this fall food source for at least three nights, which is when the camera memory card filled up.

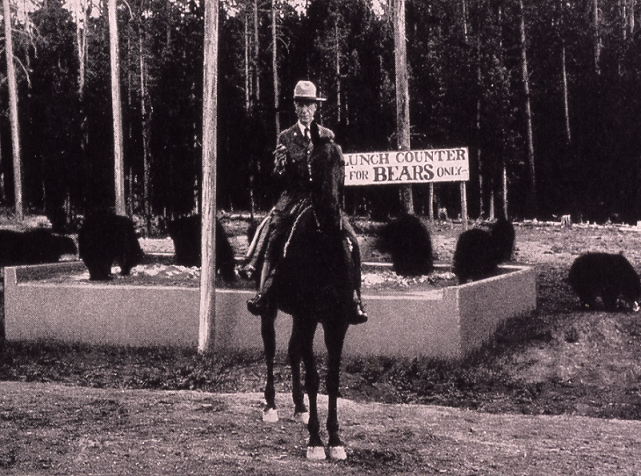

Shortly after YNP became America’s first national park in 1872, both the grizzly and black bears in the park were often fed by visitors. It was not uncommon to see bears begging by the roadside for handouts. YNP itself installed trash dumps behind the park hotels where food scraps were put out for bears to eat. Bleachers were even erected so visitors could watch the “bear show.” In the early 1970s the park ended this feeding program, but the bears had become habituated to humans and reliant on food handouts. Many bears perished in this rough transition, and by 1975 the grizzly population had dwindled to 136 bears, prompting their federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.

The bear population rebounded slowly at first, but it continued to grow as this resilient species relearned natural food sources. In 2007, the US Fish and Wildlife Service deemed their recovery complete, and the Yellowstone grizzly was removed from the endangered species list. Their management was returned to the states.This didn’t last long, though: by 2009, the grizzlies were bumped back to federal management, primarily because of a lawsuit that argued successfully that the bear’s food sources were insecure enough to threaten the long-term health of the population. The mortality of whitebark pines due to mountain pine beetles (a native bark beetle) and white pine blister rust (a non-native fungal pathogen) was the biggest issue, for this threatened the long-term availability of the pine nut, an important fall food source prior to hibernation. The bears have been federally protected since then, but that looks like it’s about to change.

The bear population rebounded slowly at first, but it continued to grow as this resilient species relearned natural food sources. In 2007, the US Fish and Wildlife Service deemed their recovery complete, and the Yellowstone grizzly was removed from the endangered species list. Their management was returned to the states.This didn’t last long, though: by 2009, the grizzlies were bumped back to federal management, primarily because of a lawsuit that argued successfully that the bear’s food sources were insecure enough to threaten the long-term health of the population. The mortality of whitebark pines due to mountain pine beetles (a native bark beetle) and white pine blister rust (a non-native fungal pathogen) was the biggest issue, for this threatened the long-term availability of the pine nut, an important fall food source prior to hibernation. The bears have been federally protected since then, but that looks like it’s about to change.

It seems likely that the grizzly bear will be removed from federal protection within the next year, as demographic benchmarks in the grizzly bear management plan have been met for a number of years. Furthermore, the grizzly interagency management team has found that, despite the decline of important food sources, the grizzly bear is adaptable enough to continue to survive and reproduce. For some, this is a vindication of the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act. For others, it will be a very sad day to see management turned over to states, which are likely to manage the population with a legal hunt.

It seems likely that the grizzly bear will be removed from federal protection within the next year, as demographic benchmarks in the grizzly bear management plan have been met for a number of years. Furthermore, the grizzly interagency management team has found that, despite the decline of important food sources, the grizzly bear is adaptable enough to continue to survive and reproduce. For some, this is a vindication of the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act. For others, it will be a very sad day to see management turned over to states, which are likely to manage the population with a legal hunt.

In 2012, after the grey wolf lost its federal protection in Wyoming, the state’s Game and Fish Department instituted the first legal wolf hunt since 1926, when wolves were extirpated from YNP. During the hunt, a number of beloved and famous wolves were killed when they ventured beyond the invisible border of the national park. This caused an uproar in the conservation community and likely contributed to a lawsuit that put the wolves back under federal protection in 2014.

In 2012, after the grey wolf lost its federal protection in Wyoming, the state’s Game and Fish Department instituted the first legal wolf hunt since 1926, when wolves were extirpated from YNP. During the hunt, a number of beloved and famous wolves were killed when they ventured beyond the invisible border of the national park. This caused an uproar in the conservation community and likely contributed to a lawsuit that put the wolves back under federal protection in 2014.

Will the grizzly see the same fate? In an unprecedented move, the superintendents of both Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks have expressed their concern about the potential harvest of grizzly bears adjacent to the national parks. Famous bears like 399 and 610 would be quite vulnerable if a legal hunt were allowed outside the national parks, as they spend considerable time by roads, have become somewhat habituated to humans, and often cross outside of national park boundaries.

It is hard to argue against the numerical recovery of the grizzly; the criterion for delisting has clearly been met. But it is also hard to imagine the optics and reality of famous and revered bears being legally hunted in areas where they have been protected for their entire lives.

Will we learn from the recent experience of the grey wolf delisting? My hope is that our management system has the foresight and flexibility to allow the Endangered Species Act to work, while at the same time protecting vulnerable and valuable wildlife from a drastic rule switch that, if not done properly, could result in the demise of America’s most famous grizzlies.

Information in this blog from: https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/esa_works/northwest.html; http://www.nps.gov/features/yell/slidefile/mammals/blackbear/Page-5.htm; C.C. Schwartz, M.A. Haroldson, and K. West, editors.Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2004. USGS, Bozeman, Montana.