Teman Cooke, who holds a PhD in theoretical physics, is nervous about the future of science. In the TED talk he gave in 2014 he warned us that, “As a culture, as a civilization, we fear science.” And he has three ideas as to why: We are obsessed with right answers and afraid of being wrong. We are obsessed with conclusions. And we are very aware that our conclusions can change. All the time. Remember when Pluto was a planet?

We fear science so much that, in a survey of 2,000 parents, 50% say they fear answering their children’s questions about science. Questions like: Why can’t we fly? Why is it cold? Why is the sky blue? Where does the sun go at night time? Perhaps the scarier statistic is that 20% of these 2,000 parents respond to such questions with either made up answers or simply claim ‘nobody knows.’

We fear science so much that, in a survey of 2,000 parents, 50% say they fear answering their children’s questions about science. Questions like: Why can’t we fly? Why is it cold? Why is the sky blue? Where does the sun go at night time? Perhaps the scarier statistic is that 20% of these 2,000 parents respond to such questions with either made up answers or simply claim ‘nobody knows.’

Part of the problem is the way we grow up surrounded by subtle messages that science is only reserved for certain people, and that only those certain people can tackle the complexities inherent to science because ‘science is hard.’ Even the ‘look’ of a scientist is seemingly hard to master and can feel exclusive. So how can we tweak those rigid messages about science that our children are receiving? Children, like their parents, are eager to make sense of the world around them. Unlike their parents, they are enticed by complexities and unknowns, not scared of them. They see the world as waiting, arms open, to be explored and questioned. And all too often, our society responds to such excitement by saying ‘don’t touch,’ ‘don’t play,’ ‘don’t question.’

Here at Teton Science Schools, we acknowledge the vastness of science and hope to provide students with the tools they need to make sense of this world at least a little bit. And to begin that process of building their scientific toolkits, we must first have an understanding of what their perception of science is so as to extend and, potentially, redefine it.

Here at Teton Science Schools, we acknowledge the vastness of science and hope to provide students with the tools they need to make sense of this world at least a little bit. And to begin that process of building their scientific toolkits, we must first have an understanding of what their perception of science is so as to extend and, potentially, redefine it.

But first, what is science? This is an important question to us instructors, one we typically ask students on our first morning before we head out into the field for the day. Science is in our name, so naturally students have expectations about what they will learn and do here before they even drive up Coyote Canyon and arrive on our campus. Our next move is an equally important one: “What does a scientist look like?”

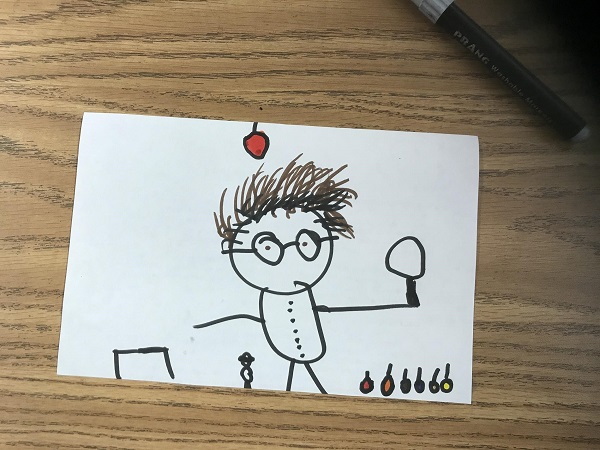

If we ask students to sketch their answer to that second question, we get a lot of stick figures surrounded by stars or wild animals, perhaps faces pressed firmly against telescopes or binoculars. Sometimes we get a Jane Goodall-type, notebook in hand, wide-brimmed hat. Maybe we get someone kneeling by a river looking at bugs. Unfortunately, though, most of the time we get some old guy with crazy grey hair, a white lab coat, and test tubes falling out of his pockets. And, unfortunately, it is almost always a guy, regardless of who is drawing it. And that is frustrating. It is one thing to have students identify as a scientist (a greater goal of ours for the week), but it is almost a harder and more important mission for us to merely break down that norm. Science is….ready, set, explore.

If we ask students to sketch their answer to that second question, we get a lot of stick figures surrounded by stars or wild animals, perhaps faces pressed firmly against telescopes or binoculars. Sometimes we get a Jane Goodall-type, notebook in hand, wide-brimmed hat. Maybe we get someone kneeling by a river looking at bugs. Unfortunately, though, most of the time we get some old guy with crazy grey hair, a white lab coat, and test tubes falling out of his pockets. And, unfortunately, it is almost always a guy, regardless of who is drawing it. And that is frustrating. It is one thing to have students identify as a scientist (a greater goal of ours for the week), but it is almost a harder and more important mission for us to merely break down that norm. Science is….ready, set, explore.

By the end of our time with these students, hopefully they have at least started to expand their definition of science and grasped the accessibility of it. Hopefully they can leaf through their field journal when they return home and recall the smell of the Lodgepole Pine they sketched like a naturalist, zooming in on the needles and labeling with descriptions of texture and color. Maybe after school they choose to collect bugs in the nearby stream instead of going to their rooms, closing the door, and watching Netflix while they’re supposed to be doing homework. Perhaps, over dinner, they share the story of the pika losing its habitat because of climate change. Perhaps they share their innovative solution to this problem.

By the end of our time with these students, hopefully they have at least started to expand their definition of science and grasped the accessibility of it. Hopefully they can leaf through their field journal when they return home and recall the smell of the Lodgepole Pine they sketched like a naturalist, zooming in on the needles and labeling with descriptions of texture and color. Maybe after school they choose to collect bugs in the nearby stream instead of going to their rooms, closing the door, and watching Netflix while they’re supposed to be doing homework. Perhaps, over dinner, they share the story of the pika losing its habitat because of climate change. Perhaps they share their innovative solution to this problem.

In America today, only 6% of 24 year olds are in fields of math or sciences. That is low, and that is also scary. It’s scary when we think about the fields that need our brains, the fields that ask tough questions and develop creative answers, the fields that allow us to experiment and fail fast and try again. It’s scary when we think about the minds needed to solve the problems of natural disasters, habitat degradation, overpopulation, food scarcity, public health, global terrorism…the list goes on. So why is science seen as scary, and how can we adjust our mindsets, our pedagogy, and our culture to embrace the challenge of science and recognize science for what it is?

I recently asked a local 5th grader how she defines science. “Ugh I hate science!” She said with a giggle. “I’m bad at it! But I was a scientist for Halloween! I wore a white lab coat and I had a lot of test tubes in my pockets. It was cold.” I remember my perception of science at that age was not too different. My sentiment towards science didn’t change much until college, when I learned the true breadth that exists within the scientific field. I was that student who loved to ask the Whys, Hows, What Ifs, and Why Nots of life, but I was also too scared to speak up in science class because my questions, I thought, had to be more concrete than that.

I recently asked a local 5th grader how she defines science. “Ugh I hate science!” She said with a giggle. “I’m bad at it! But I was a scientist for Halloween! I wore a white lab coat and I had a lot of test tubes in my pockets. It was cold.” I remember my perception of science at that age was not too different. My sentiment towards science didn’t change much until college, when I learned the true breadth that exists within the scientific field. I was that student who loved to ask the Whys, Hows, What Ifs, and Why Nots of life, but I was also too scared to speak up in science class because my questions, I thought, had to be more concrete than that.

I am grateful for the ways science has been redefined for me during my tenure at TSS. As educators, students, parents and mere participants in this confusing and complicated world, let’s be brave in our encounters with science. Let’s be persistent with our Why Nots and What Ifs, and let’s embrace the exploration it will take to generate such questions. Let’s take the advice of one TSS staff member, Josh Kleyman: “At its roots science is about observation and questioning, it’s not as much about understanding a fact but it’s about being involved in the world, understanding what you see, asking questions and using a process to begin developing answers to those questions.”

Ready, set…touch, play, question, explore.