That it was ten o’clock on a Wednesday was irrelevant when we crested Guilbeau Pass. We were radiating holiday spirit on that day, because it was our 25th day walking through the Arctic, and because the tussocks that sometimes aggravated our ankles were looking quite festive covered in snow. We had been following caribou tracks since leaving the Hula-Hula River two days earlier, and their knowledge of the scree fields and braided rivers relieved us of route finding for a bit, allowing us to mindlessly follow their paths. Sometimes, in wetter areas, their footsteps were shrouded with rainbow tints, and we wondered if this was residue from their fur or evidence of the politically precious sinks we knew lay beneath us.

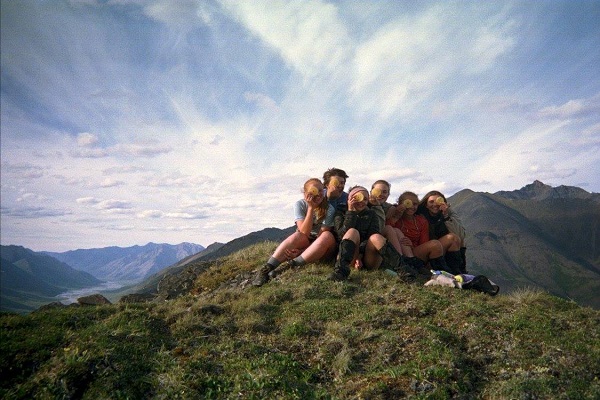

In addition to exchanging gifts on our makeshift Christmas (water-colored cards, pressed bluebells, coupons for foot massages, heart-shaped cobbles), we celebrated the day with half-baked gingerbread and a scramble up the towering scree field in our campsite’s backyard. We found the slope’s snowfields easier to traverse than the unconsolidated rocks, and the fresh grizzly bear scat on the snow suggested that the animals thought so too. Amelia tried sledding. Maia sang the harmony of our favorite Beyonce tune. Sophie made a snow-cone in her Nalgene. Nina rehearsed last spring’s ballet routine. We basked in all of these simple things, entirely detached from deadlines and social angst, feeling grateful for the unending tundra we could walk along, beneath the Arctic sun that never set. The only limitations of the moment were our grumbling stomachs and the increasing volume and decreasing altitude of those clouds. We summited the peak and reveled in the likelihood that no one else had stood here, nor had seen this.

In addition to exchanging gifts on our makeshift Christmas (water-colored cards, pressed bluebells, coupons for foot massages, heart-shaped cobbles), we celebrated the day with half-baked gingerbread and a scramble up the towering scree field in our campsite’s backyard. We found the slope’s snowfields easier to traverse than the unconsolidated rocks, and the fresh grizzly bear scat on the snow suggested that the animals thought so too. Amelia tried sledding. Maia sang the harmony of our favorite Beyonce tune. Sophie made a snow-cone in her Nalgene. Nina rehearsed last spring’s ballet routine. We basked in all of these simple things, entirely detached from deadlines and social angst, feeling grateful for the unending tundra we could walk along, beneath the Arctic sun that never set. The only limitations of the moment were our grumbling stomachs and the increasing volume and decreasing altitude of those clouds. We summited the peak and reveled in the likelihood that no one else had stood here, nor had seen this.

When we think and teach about conservation at the Teton Science Schools, we often gravitate towards the legacy of Mardy Murie, to her connection and commitment to places untrammeled, and to her heartfelt recounts of life in Jackson Hole and Alaska. She was a woman who found traction and a sturdy stance in spaces where she felt impassioned, and, as Terry Tempest Williams states, “her commitment to relationships, both personal and wild, has fed, fueled, and inspired an entire conservation movement.”

When we think and teach about conservation at the Teton Science Schools, we often gravitate towards the legacy of Mardy Murie, to her connection and commitment to places untrammeled, and to her heartfelt recounts of life in Jackson Hole and Alaska. She was a woman who found traction and a sturdy stance in spaces where she felt impassioned, and, as Terry Tempest Williams states, “her commitment to relationships, both personal and wild, has fed, fueled, and inspired an entire conservation movement.”

At the Murie Museum on the Kelly Campus, students can learn about Mardy and her husband Olaus’ relationship with science through explorations of their specimen collection and hand-drawn species accounts. At the Murie Center in Moose, students can walk the two-miles that 80-year-old Mardy skied each morning to get her mail. They can sit on the porch that witnessed the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964. They can admire paintings that depict Mardy’s ventures through the Brooks Range. They can read the accompanying stories about the ways Mardy thrived and found purpose and awe in her “place of enchantment.”

Mardy reflects on her days in the far North: “…it was a world that compelled all our interest and concentration and put everything else out of mind. As we walked over the tundra, our attention was completely held by the achievements of that composition of moss, lichens, small plants, and bright flowers, yet we were ever on the alert to identify every bird, to note every evidence of bears- moss and roots dug up, tracks in the mud at the edge of pools. How could we be anything but absorbed?”

Mardy reflects on her days in the far North: “…it was a world that compelled all our interest and concentration and put everything else out of mind. As we walked over the tundra, our attention was completely held by the achievements of that composition of moss, lichens, small plants, and bright flowers, yet we were ever on the alert to identify every bird, to note every evidence of bears- moss and roots dug up, tracks in the mud at the edge of pools. How could we be anything but absorbed?”

My jaunt with 6 other young women through the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge this past summer came many decades after Mardy’s. Our gear included Gore-Tex rain jackets, portable backpacking stoves, and concentrated pepper spray to fend off large mammals.  We had a satellite phone and a personal locating beacon just in case the surf became too tumultuous. Dirk, our bush pilot, brought us fresh rations of extra-crunchy peanut butter, quinoa, and soap on days 11 and 23 of our trek. However, these things, luxurious in comparison to Mardy’s, were still rudimentary. They didn’t protect us from frozen shoelaces, tattered tent flies, unrelenting rain, distance from people we love, mosquitos, or monotony.

We had a satellite phone and a personal locating beacon just in case the surf became too tumultuous. Dirk, our bush pilot, brought us fresh rations of extra-crunchy peanut butter, quinoa, and soap on days 11 and 23 of our trek. However, these things, luxurious in comparison to Mardy’s, were still rudimentary. They didn’t protect us from frozen shoelaces, tattered tent flies, unrelenting rain, distance from people we love, mosquitos, or monotony.

But, like Mardy, we cherished the discomfort and the simplicity. I think the deep contentment we found in the Brooks Range had a similar color to the fondness that led Mardy to commit her life to preserving this place. We found it in the moments when we threw our packs to the ground after a long day, and a piece of land, a previously insignificant space, became our home, that grassy patch over yonder the kitchen. We found it in the constant sense of purpose; whether we were hiking over a pass, doing camp chores, finding a five-star bathroom, or flipping pancakes on a rainy morning. We found it in the space and ability to disconnect, to feel free and wild and empowered, to live slowly and with intention, to bask, and to wander.