On the last day of our third place-based education workshop in Bhutan this past January, staff from the Royal Education Council were immersed in a flurry of sticky notes and passionate conversation. We had presented them with a real-world problem: In the past, winter snowfall and seasonal glacial melt has allowed Bhutan to generate hydropower for use in-country. But Bhutan has lost 20% of its glaciers in the last 20 years. Climate change is altering the flow of rivers in Bhutan, and hydropower is becoming risky and unreliable. In addition to hydropower, Bhutan relies heavily on fossil fuel imports from India, including vehicles, diesel fuel, and power.  As climate change increases, Bhutan’s reliance on imported fossil fuels will increase. So will the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere, compounding the issue. Bhutan needs a way to change its import/export patterns to reduce the country’s risk from climate change and its over-reliance on India.

As climate change increases, Bhutan’s reliance on imported fossil fuels will increase. So will the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere, compounding the issue. Bhutan needs a way to change its import/export patterns to reduce the country’s risk from climate change and its over-reliance on India.

Participants in the workshop took to generating solutions with gusto. Their energetic brainstorming gradually boiled down to presentations of each group’s winning idea for positive change. We heard proposals for sustainable housing projects, changing the mindset of the government, and agricultural practices nurtured through school and community partnerships.This exercise gave the Royal Education Council staff a taste of the design process, which is one of the core principles of place-based education.  Since they write curriculum for the country and train its teachers, we wanted them to practice with a scenario that could be implemented in Bhutanese classrooms.

Since they write curriculum for the country and train its teachers, we wanted them to practice with a scenario that could be implemented in Bhutanese classrooms.

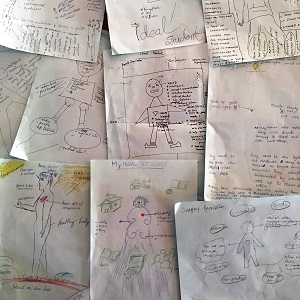

Educational professionals that we spoke with in Bhutan want to nourish students’ problem-solving abilities. When asked to draw what their “ideal student” would look like after a year of class with them, participants at our workshops depicted compassionate children who were creative, critical thinkers with real-world skills. The experiential nature of place-based education can create students with these qualities, providing their teachers have the tools and support to facilitate this type of learning.

The Royal Education Council and the Ministry of Education are making significant efforts to better equip teachers to engage students. TSS has been working with them to integrate place-based education into curriculum and teacher training since 2008. In addition, they recently launched a training initiative for all 11,000 teachers across the country dedicated to transforming the existing pedagogy into a more learner-centered format.This signifies a step away from the lecture-based style that has previously been the norm in Bhutan, and a step toward those “ideal students.”

The Royal Education Council and the Ministry of Education are making significant efforts to better equip teachers to engage students. TSS has been working with them to integrate place-based education into curriculum and teacher training since 2008. In addition, they recently launched a training initiative for all 11,000 teachers across the country dedicated to transforming the existing pedagogy into a more learner-centered format.This signifies a step away from the lecture-based style that has previously been the norm in Bhutan, and a step toward those “ideal students.”

Bhutan’s philosophy of Gross National Happiness emphasizes sustainable growth, good governance, and preservation of culture. These admirable and lofty goals give these educators a vested interest in creating the “ideal student.” Students who can think critically and have a deep understanding of where they live can help build the happy nation that Bhutan dreams of being.TSS looks forward to continuing its support of Bhutan in educating for Gross National Happiness in the years ahead. We also want to be sure to celebrate each step forward along the way. Lhundup Dukpa of the Royal Education Council put it best: “Happiness is not something out there to be achieved; we have to experience it as we go along.”