Imagine this scenario. You’re a new middle school student, excited to dive into biology class for the first time. You arrive to class on the first day and receive your text book–the same text book that has been used in your elementary school classes for the last three years. After a few introductory notes, the teacher passes out the syllabus for the first quarter: cell anatomy, genetics, and evolutionary history. The field trips and assignments haven’t changed since your sibling did them a few years back. After a few weeks, class doesn’t have the same allure as it did and the planned field trips and projects stir up more feelings of dread than excitement. You’re bored and going through the motions.

Now imagine this. You’re a new middle school student, excited to dive into science for the first time as a middle schooler. You arrive to class on the first day and the teacher asks you and the other students to brainstorm EVERYTHING that you’re curious about when it comes to science. You add to the board things like: Why doesn’t it snow as much anymore? How do plants eat? How are animals related to each other? And anything to do with the night sky — you love it! After a few class periods of discussion, your class and teacher decide to dive into science through the lens of ecology. She invites a local expert from the zoo to your classroom to talk about animal diversity; later on you’ll get to visit the zoo in person with your classmates. Your teacher helps you create a driving question that will influence the next few months in class. You’re excited, engaged and invested in your work!

If you felt more inspired as you read through the second scenario, there’s a good reason. It described what students might experience in a place-based classroom engaging in science through project-based learning (and how it’s never the same). For our students here at Mountain Academy, and within the schools that make up our Place Network, this is the type of learning students are engaged in every single day. Before we dive into some exemplary projects, let’s explore some of the foundations of Project-Based Learning.

What is Project-Based Learning?

Buck Institute for Education (BIE) defines Project-Based Learning as:

“A teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge.”

In simpler terms, Project-Based Learning is when students work for an extended period of time on a project that engages them in real-world learning and authentic problem-solving. And, it’s different from simply including projects in traditional textbook units. How?

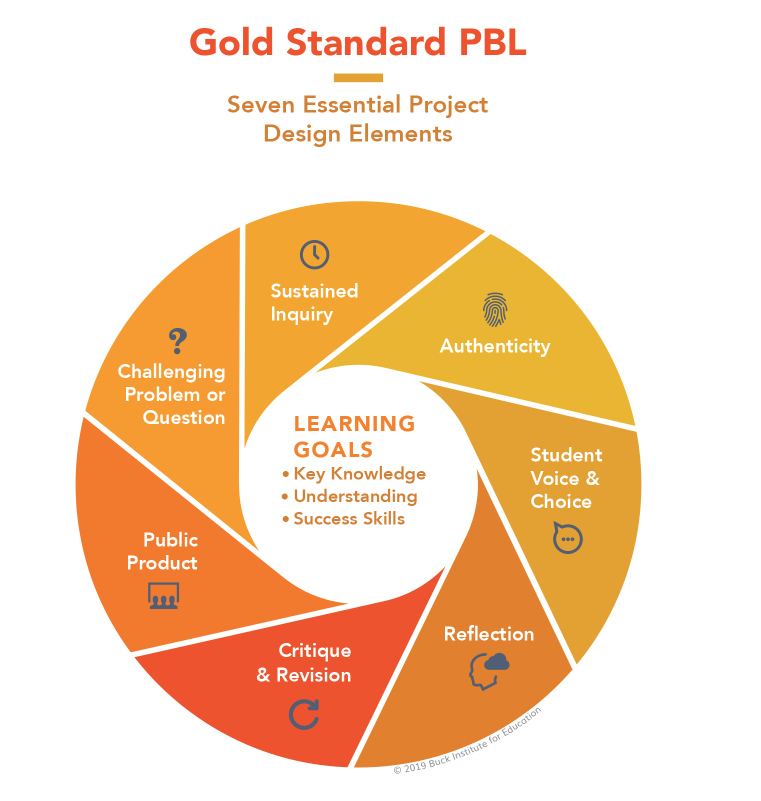

There are key characteristics that differentiate a traditional “school project” from rigorous and engaging Project-Based Learning. BIE finds it helpful to distinguish the two by categorizing them as either as “dessert project” — a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way — or a “main course” project, where the project is the unit and requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication (source).

Key characteristics according to Gold Standard Project-Based Learning include:

- A challenging problem or question: The project is framed by a meaningful problem to be

solved or a question to answer, at the appropriate level of challenge.

solved or a question to answer, at the appropriate level of challenge. - Sustained inquiry: Students engage in a rigorous, extended process of posing questions, finding resources, and applying information.

- Authenticity: The project involves real-world context, tasks and tools, quality standards, or impact, or the project speaks to personal concerns, interests, and issues in the students’ lives.

- Student voice and choice: Students make some decisions about the project, including how they work and what they create.

- Reflection: Students and teachers reflect on the learning, the effectiveness of their inquiry and project activities, the quality of student work and obstacles that arise and strategies for overcoming them.

- Critique and Revision: Students give, receive, and apply feedback to improve their process and products.

- Public Product: Students make their project work public by explaining, displaying and/or presenting it to audiences beyond the classroom.

So how does it all come together?

Let’s dive into a couple of student projects to explore how students guided their study of science in different ways.

Project #1: Using Biology to Influence Politicians

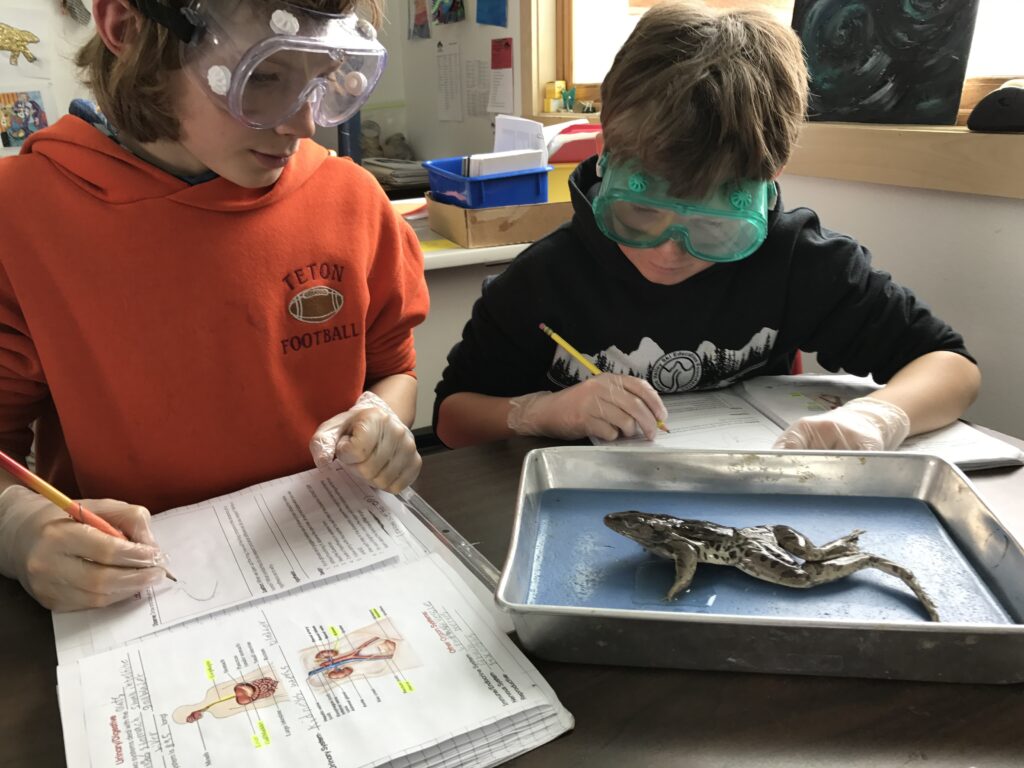

In 2017, fifth-seventh grade students at the Teton Valley Campus of Mountain Academy explored their interest in ancestry, animals and biology by developing an interdisciplinary project that took them all the way to their state capitol building. To get there, the class started with what they knew, what they wanted to know and built initial background knowledge around cell biology, anatomy and genetics.

At this point, the shape of their project wasn’t yet formalized. According to their teacher, now Mountain Academy Associate Head of School, Elle Shafer, student indecision posed a challenge early on. She explains:

“After building initial background knowledge around biology, students weren’t sure what direction to go next and they wanted teachers to direct them. As the teacher I wanted to say, “Remember, you’re in charge! You get the voice and choice! What should we do with our learning?” But that didn’t feel like an encouraging approach. Instead, I stepped back and decided that we should spend a few class periods talking about what we had learned and what we wanted to DO with that learning. It turned out that that process was exactly what students needed — to take a breath, step back, and reflect before moving forward with making decisions. From there, we took this amazing turn to bald eagles and then more broadly raptors and then raptor safety in the Snake River Watershed…and the rest is history!”

With an authentic driving question in hand — How can we use our biology background knowledge to influence politicians on the effects that humans have on the avian life in the Snake River Watershed? — students built knowledge and skills through inquiry, and developed skills and dispositions through student-driven design thinking, critique and revision.

As their final public product, students designed an avian awareness solution that was two-fold:

-

-

- Locally, they hosted a community-wide road clean-up day where they supervised event logistics — pre-event communications, collecting forms & waivers, and a media campaign — from start to finish.

- Statewide, they advocated for adding an avian awareness reminder to all Adopt-a-Highway signs. On April 26th, they presented their highway sign proposal to State Senator, Mark Harris, and were able to get him to agree to help them to create an avian-awareness sign that would read, “Keep your Wrapper, Save a Raptor.”

-

“Watching our students present in front of Senator Harris in our State Capitol Building about an issue that they care about was an incredibly rewarding experience–and that is what Place-Based, Project- Based Learning is all about,” reflected Shafer at the end of the project.

Project #2: A Local Investigation into Single-Use Plastics

In early 2019, second-fifth grade students at the Jackson Campus of Mountain Academy were inspired to dive into science through the lens of environmental conservation by exploring their interest in recycling, up-cycling and the recent Plastic Bag Ban passed in the City of Jackson (Voice & Choice, Authenticity).

After formulating their driving question — How can our community impact the use of single use plastics? — students engaged in a process of sustained inquiry and constructive critique. Students researched single-use plastics and the plastic bag ordinance, collected data on their own use of single-use plastics, solicited input from the greater community about single-use plastic and the placement of refillable water bottle stations, and generated solutions for meaningful community impact.

As their final public product, students determined two methods for reducing the impact of single-use plastics in their community:

-

-

- Participating in the distribution of reusable grocery bags to community members affected by the plastic bag ban.

- Raising awareness on the impact of single-use plastics through education campaigns and writing letters to local and national businesses.

-

As we can see from the above project examples, the way students engage with and retain knowledge around science can vary immensely based on things like student interest, local issues and the scientific lens through which both are approached. In place-based classrooms, it’s never really the same. What is the same is an approach to learning: a motivating and highly energizing approach for students that also prepares them with the skills, mindsets, and personal agency for future success in school, life and in their community.